|

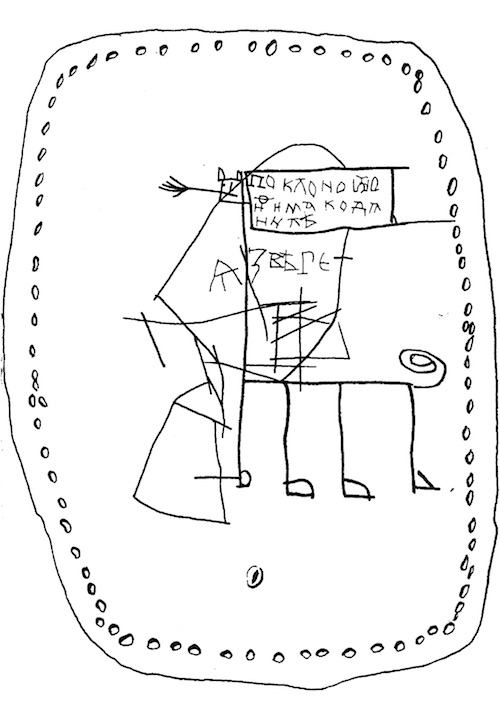

| Gramota No. 200. |

In the annals of history, the lives of ordinary people, particularly children, often remain shrouded in mystery. Their stories, if not entirely lost, are typically overshadowed by the grand narratives of kings, wars, and religious movements. However, in the case of a young boy named Onfim, who lived in the 13th century in Novgorod, Russia, we are granted a rare glimpse into the life of a medieval child through an extraordinary collection of birchbark documents. These documents, known as “birchbark manuscripts,” were discovered in the 20th century, revealing a treasure trove of drawings and writings that provide insight into the thoughts, education, and daily life of a young boy living nearly 800 years ago.

This article explores the historical context of Novgorod in the 13th century, the significance of birchbark documents, and the unique story of Onfim. Through his drawings and writings, we gain a deeper understanding of medieval childhood, literacy, and the cultural environment of Novgorod, a major center of trade and learning in medieval Russia.

During the 13th century, Novgorod was one of the most significant cities in medieval Russia. Located in the northwest, near modern-day St. Petersburg, Novgorod was a thriving center of commerce, culture, and political power. It was part of the Hanseatic League, a powerful commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Northwestern and Central Europe. This connection facilitated trade between Novgorod and other major European cities, making it a cosmopolitan hub where ideas, goods, and people converged.

Novgorod was also unique in its system of governance. Unlike many other medieval cities, which were ruled by princes or kings, Novgorod operated as a republic, with a system of popular assemblies known as “veche” that made decisions on matters of governance. This democratic aspect of Novgorod's society fostered a relatively high level of literacy and civic engagement among its inhabitants, which is reflected in the abundance of written records from the period.

The city was also a center of Orthodox Christianity, and its religious institutions played a crucial role in education. Boys like Onfim would have received their education in the church or under the supervision of clergy, learning to read and write in Church Slavonic, the liturgical language of the Russian Orthodox Church. This education was not limited to religious texts but also included writing exercises, some of which have been preserved in the form of birchbark manuscripts.

The birchbark manuscripts of Novgorod are among the most significant archaeological discoveries in medieval Russian history. These documents were made by inscribing letters and drawings onto strips of birchbark, a material that was readily available and relatively easy to use for writing. The practice of using birchbark for writing was common in Novgorod from the 11th to the 15th centuries, and over 1,100 such manuscripts have been discovered since the first were unearthed in 1951.

The preservation of these documents is largely due to the unique soil conditions in Novgorod, where the high water table and anaerobic environment prevented the decay of organic materials. As a result, these birchbark manuscripts provide an unparalleled glimpse into the everyday lives of the people of medieval Novgorod, including their language, education, and personal communications.

The content of the birchbark manuscripts varies widely, ranging from legal documents and business transactions to personal letters and educational exercises. Among these, the writings and drawings of Onfim stand out as particularly remarkable. Onfim's manuscripts consist of a series of drawings and writing exercises that offer a rare and intimate look at the thoughts and creativity of a medieval child.

Onfim, who was likely around 6 or 7 years old at the time he created his birchbark documents, was a typical boy of his era in many ways. He was learning to read and write, probably under the guidance of a tutor or in a church school. His writings show that he was practicing the alphabet and basic phrases, a common exercise for children of his age in medieval Novgorod.

What makes Onfim's manuscripts extraordinary, however, is the combination of text and illustrations. Alongside his writing exercises, Onfim filled the birchbark with drawings that reveal his vivid imagination and the world as he saw it. His drawings include depictions of knights, battles, animals, and even self-portraits, often accompanied by simple sentences or phrases.

One of Onfim's most famous drawings shows a figure that scholars believe to be a self-portrait, labeled “Onfim.” The figure is depicted as a knight on horseback, holding a spear and shield. This image suggests that Onfim, like many children, was fascinated by the idea of heroism and adventure, perhaps inspired by the stories and legends he heard or read.

In another drawing, Onfim depicted a scene of combat, with one figure standing over another, victorious. This image, too, reflects the martial culture of medieval Novgorod, where the threat of conflict was a constant reality, and young boys were likely exposed to stories of battles and warriors from an early age.

|

| Gramota No. 199. |

But Onfim's drawings also reveal a tender side. In one birchbark manuscript, he wrote “I am a wild beast” and drew an image of a creature, possibly a representation of himself as a playful or mischievous figure. This combination of words and images shows how Onfim used his burgeoning literacy to express his imagination and personality, blurring the lines between learning and play.

The writings and drawings of Onfim are significant for several reasons. First, they provide a unique glimpse into the life of a medieval child, a perspective that is rarely preserved in historical records. Onfim's manuscripts show that children in medieval Novgorod were not so different from children today—they were curious, imaginative, and eager to express themselves through both words and art.

Second, Onfim's manuscripts highlight the importance of education in medieval Novgorod. The fact that a child of his age was already practicing writing and creating drawings on birchbark suggests that literacy was valued, even among the young. This emphasis on education was likely connected to Novgorod's status as a major cultural and religious center, where literacy was essential for participation in civic and religious life.

Third, Onfim's drawings offer insight into the cultural and social environment of medieval Novgorod. His depictions of knights and battles reflect the martial culture of the time, while his playful self-portraits propose a world where children were encouraged to engage with their surroundings creatively. The combination of text and images in Onfim's manuscripts also suggests that medieval education was not limited to rote learning but included opportunities for creative expression.

Finally, Onfim's manuscripts are valuable for what they tell us about the use of birchbark as a medium for writing. The fact that Onfim's writings and drawings have survived for nearly 800 years is a testament to the durability of birchbark and the importance of everyday materials in preserving history. These documents remind us that history is not just about great events and famous figures, but also about the ordinary people who lived, learned, and created in their own time.

Onfim's manuscripts have had a lasting impact on our understanding of medieval childhood and education. Since their discovery, they have been studied by historians, archaeologists, and linguists, who have used them to gain insight into the daily life and culture of medieval Novgorod. Onfim's drawings, in particular, have captivated scholars and the public alike, offering a rare and charming window into the mind of a medieval child.

In recent years, Onfim has become something of a cultural icon in Russia and beyond. His drawings have been featured in exhibitions, books, and educational materials, serving as a reminder of the continuity of childhood across the centuries. Onfim's work has also inspired contemporary artists and educators, who see in his manuscripts a connection between past and present, and a reminder of the timelessness of human creativity.

Onfim's legacy also extends to the field of archaeology, where his manuscripts have played a key role in the study of birchbark documents. The discovery of Onfim's writings has led to renewed interest in the use of birchbark as a writing material and has prompted further excavations in Novgorod and other areas where similar documents might be found. These discoveries continue to enrich our understanding of medieval literacy and the everyday lives of ordinary people.

The story of Onfim is a testament to the power of ordinary voices in history. Through his birchbark manuscripts, we are given a rare glimpse into the life of a medieval child, one who lived, learned, and imagined in a world far removed from our own. Onfim's writings and drawings reveal the vibrancy of medieval Novgorod, a city where education, culture, and creativity were highly valued.

Onfim's manuscripts also challenge us to reconsider our understanding of the past, reminding us that history is not just the story of great events and famous figures but also of ordinary people—children included—whose lives and thoughts have shaped the world in ways both large and small. In Onfim's playful drawings and simple writings, we see the timelessness of childhood and the enduring human desire to create, express, and connect.

As we continue to study and learn from Onfim's manuscripts, we are reminded of the importance of preserving and cherishing the voices of the past, for they offer us not only a window into history but also a mirror in which we can see our own humanity reflected.

Sources

Franklin, Simon, and Jonathan Shepard. The Emergence of Rus 750-1200. Longman, 1996.

Hamilton, Bernard. The Medieval Inquisition. Hodder Arnold, 1981.

Ostrowski, Donald. The Pověst’ vremennykh lět: An Interlinear Collation and Paradosis. Harvard University Press, 2003.

Pliguzov, Andrey V. "Birchbark Documents: Window into Old Russia." Harvard Ukrainian Studies, vol. 22, no. 3/4, 1998, pp. 395-421.

Smith, Justine E. H. “Onfim Wuz Here: On the Unlikely Art of a Medieval Russian Boy.” Literary Hub (blog), February 26, 2018. https://lithub.com/onfim-wuz-here-on-the-unlikely-art-of-a-medieval-russian-boy/.

Thier, Alice Isabella Sullivan. "Children in Medieval Novgorod: The Birchbark Manuscripts of Onfim." Journal of Medieval History, vol. 42, no. 2, 2016, pp. 180-204.

Zimonin, V. P. Novgorod Birchbark Documents: Everyday Life in Medieval Russia. Novgorod State Museum, 2004.

Comments

Post a Comment